Dougal and the Blue Cat

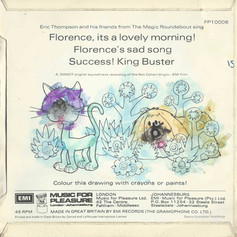

One of the more interesting children's discs to come my way is this three-track E.P. of songs from the film Dougal and the Blue Cat (Surprise Surprise FP 10006, 1972).

Released in 1972, Dougal and the Blue Cat is a full-length spin-off from Serge Dinot's The Magic Roundabout (Le Manège Enchanté) television series. It has been described as 'a bizarre film [that] treads a fine line between being charming and genuinely chilling' and 'one of the creepiest films ever made'. It references A Clockwork Orange, 2001: A Space Odyssey and NATO, features a torture scene and a 'drug' trip. For an off-shoot of a series aimed primarily at children, Dougal and the Blue Cat is an unusually 'grown-up' piece of work. Clearly, the dark, twisted plot and the sophisticated (for the time) and creative animation play a big part, but I argue that the songs contribute significantly as to why this obscure and for years out-of-print film is so fondly remembered. I suggest it's that magic combination of the musical signifiers of 'childness' (Peter Hollindale, 1997) and 'adultness' that allowed children to access and connect with the songs in the first place, and that allows adults to dive back in and pull out something genuinely meaningful nearly 50 years later.

Here's the plot: 'Life at the Magic Roundabout is disrupted when a blue cat called Buxton finds his way into town. Everyone loves Buxton except for Dougal, who discovers the cat's mad plan to become the king of blue army and destroy all who are not blue'.

Replace Dougal with The Beatles and it's nearly the Yellow Submarine film plot.

However, it's the record and three soundtrack songs that most interest me. The music of the Dougal and the Blue Cat songs was composed by prolific French accordionist Joss Baselli (100+ albums to his name!), with lyrics and singing by Eric Thompson, (A Play School presenter at the time, Eric was father of Harry Potter and Nanny McPhee actor Emma Thompson, fact fans). Thompson claims never to have read the translations of the original French scripts or had any clue as to the plot lines. His new stories and scripts often worked around the visuals rather than with them, adding to the otherworldly sense of surrealism often associated with The Magic Roundabout.

The first song is: 'Florence. It's a lovely morning'.

The song twinkles with 'childness'. The high melodic strings, delicate glockenspiel and gentle woodwind are strong signifiers, as are the explicit repetition of perfect rhyme ('dust dust dust', 'must must must'). There's an intertextual reference to age-undifferentiated fairy tales ('Mirror, mirror on the wall. Who's the fairest one of all?') and a couple of minor chords to temper the major. The song bursts with the assertive charm of young woman who would rather 'wander' than do the housework, no matter how much the narrator implores ('it's a living wonder that your house is not now under a great big cloud of dust'). But as they seems to be loosing their rag towards the end ('Florence, will you come back here? There's none so deaf as will not hear'), Florence has left her chores far away ('Now she's gone for good, I fear').

Next up is 'Florence's Sad Song'.

Whilst the instrumentation is similar to 'Florence. It's a lovely morning', 'Florence's Sad Song' is down tempo with the long, sad minor key sections only breaking to the (parallel) major when Florence says 'It must all be a dream'. The lyrics are unremittingly existential and self-doubting. They allude to a fear of being stuck forever in a dark and lonely place, and ultimately of death ('will the games we play end here?). As the tears roll down everyone's cheeks in the film, Eric Thompson captures a rare sentiment in children's music. Through the character of Florence, he voices an acknowledgement of fear and sadness and of death whilst reflecting the loss of innocence through self-reflection and (often traumatic) experience that characterises learning and growing up ('Somehow I know it's my fault. I should have trusted no one. My trusting spoiled the game'). As a text, Dougal and the Blue Cat has built-in growing room so that adults who revisit it (or view for the first time) can harvest layers of meaning that were seeded by the film, and especially this song, the first time round.

The final song on the E.P. is 'Success! King Buxton'.

A celebratory fanfare in major then minor keys is followed by a string of boasts by the blue moggy, essentially a list of what he is King of ('all the world, even Bognor and Crewe'), how he got there ('by cleverness') and what will happen to anyone who dares deny him the throne ('get thrown in the stew'). The snare rolls and 2/4 timing are militaristic whilst the classically-inspired piano solo that Buxton performs in the film includes a brief snatch of ragtime, a vernacular interlude that, like his northern English accent (in a class-ridden and economically-divided Britain, these things are political. The town of Buxton in Derbyshire is 'northern' depending on your viewpoint), potentially reveals something of his working-class roots. Pedantically, the record sleeve calls him 'King Buster' whilst most online references call this song 'I am King'.

Film critic Mark Kermode rates Dougal and the Blue Cat as one of his favourite films (not just children's films or animated films) ever. His review contains some great clips from the film.

Few films, TV shows, books or records made for children, especially young children, contain this range of emotions. Most deliberately limit or exclude the darker end of the expressive spectrum. For example, my tentative study of the music of Barney and Friends suggests that his parma-smiling ultra-upbeat tone verges on the psychopathic. Maurice Sendak's depiction of a child's rage in Where the wild things are (watch the more recent film version trailer here) is notable as an exception. Whilst Sesame Street songs 'Bein' green' and 'Nobody' are melancholic and contemplative, they are tinged with self-acceptance and a sense of resolution. 'Florence's Sad Song' is pure abject fear. Considerations of appropriateness and of innocence and its protection run through adults' production of and reception to children's culture. In his review, Andrew Pulver said 'I don't think I'd take a little kid to see it now, at least not until they were old enough to deal with some scary nightmare scenes'. What children find upsetting is always going to be unpredictable (the eyes of a 1980s pop star poster following you round the room!). So, parents, be brave, watch Dougal and the Blue Cat with your children. Like the best children's culture it may start a conversation about some of the 'scary' stuff in the film and allow them to talk about their emotions in the context of the film. After all, a blue cat who can talk is pretty scary in itself.

The full soundtrack album and DVD are available for those who wish to hear and see more.